ZANZIBAR

HISTORY WITH ADDED SPICE

HISTORY WITH ADDED SPICE

Zanzibar, as any schoolchild could tell you, is the Spice Island; but to most of us it is a place that remains exotic, mysterious and remote. In fact, it is just a 35 minute hop by plane from Kenya coast, and an increasingly popular excursion for those enjoying a holiday at the Mombassa Inter-Continental Resort.

Although so close, Zanzibar is light years away from the modern sophistication of Mombassa. While tourism is, belatedly, on the increase and there are modern constructions, the people of Zanzibar seem to take life a little slower than most and many of the buildings ooze the island's colorful history.

Zanzibar, now a separate state within the United Republic of Tanzania, is in fact a collection of islands. Zanzibar Island, known locally as Unguju, at 50 miles long and 15 miles wide, is the largest. Pemba, to the North, is slightly smaller and the two are surrounded by a number of tiny satellite islands. The sheer physical size of the islands, however, belies the pivotal part they once played in the development of the East coast of Africa.

At the crossroads of the Indian Ocean, and probably first inhabited by Bantu speaking people, Zanzibar's first entry in European chronicles was made by a Greek pilot in the second century. Then it was discovered by the early Arabian tradesmen who were to have such an influence on shaping the history and culture of the area. The Arabs called the whole coast from Mogadishu to Mozambique, Zanzibar, the land of black people. The modified name stuck to the island which, by the eight century, already boasted substantial Arab settlements.

Exotic spices were, and still are, one of the main attractions of Zanzibar but, sadly, even in the earliest days it was often a far less pleasant commodity that drew tradesmen, of many different nationalities, in. In the ninth century the Arab historian Al Hijaz was writing of the slave trade that existed in Unguju. The islands were used as markets and holding places for the unfortunates who had been captured from the mainland interior - a practice that continued on the remoter islands even after the British in the mid nineteenth century.

Much of Zanzibar's earlier history, however, was far more positive.

The Arabs integrated well and the arrival of Islam, about 1,0000

years ago, saw the gradual flowering of the rich Swahili language

and culture. Local building materials and architectural styles

were refined and embellished under the Arabian influence. Pemba

became famous for its silversmiths whose work was in great demand

in Arabia and, always, there were the spices, in demand throughout

the know world. There were several substantial towns in the early

centuries, notably Tumbatu on Unguju; but by the fourteenth century,

Zanzibar Town was chose as the seat of the Mwinyi Mkuu rulers

of the island.

By now the wealth, and strategic position, of the islands was beginning to attract the interest of powers beyond the Middle East and India. By 1589, the Portuguese had established a garrison on Pemba, but were fiercely opposed, not only by the islanders, who were ruthlessly suppressed, but also by the people of Mombassa and Lamu. The following century was characterized by a bitter struggle against the Portuguese, until the people finally appealed to the Omanis to help them.

The Portuguese were finally defeated in their last stronghold, Mombassa, in 1698. The following years saw an influx of Omani immigrants and Zanzibar Town grew ever richer and more populous. Such was its influence that, in 1832, the ruler of Oman, Said bin Sultan, moved his headquarters to the islands. Zanzibar became the capital of Oman and the East African dominions.

All the major European powers set up consulates in Zanzibar and around this time, most of the great explorers and missionaries visited the island, and the Sultan, to ask for advice and help before their travels into the interior. The port was one of the busiest anywhere in the world.

Behind the Sultan's back, the European were constantly bickering about whose influence was greatest in the area. Zanzibar became a British Protectorate, with the Sultan as figurehead, in n1890; by 1913, all power was vested in the British Resident. Independence came in 1963, under a new Sultan, but an intolerable constitution, together with glaring social inequities, provoked a revolution in January 1964. Sheik Abeid Armani Karume became the First President of Zanzibar and before his tragic assassination in 1972, led his country into union with Tanganyika and introduced much needed and wide-ranging reforms.

In spite of its turbulent past, Zanzibar welcomes its visitors with wart and genuine interest. No longer the economic power it once was - the trade routes have long dwindled to a mere trickle - the islanders depend largely on the riches of the surrounding seas and their incredibly fertile land. Zanzibar is still the spice island and visitors are welcome at the plantations where not only cloves bu pepper, chilies, cinnamon, cardamom, turmeric, ginger, nutmeg and much more is grown in abundance. Fruit is also plentiful and, besides being a mainstay of the people's diet, it is becoming an increasingly important export. Staples such as bananas and coconuts, Seville oranges, limes and avocado pears, vie with pomegranates, rambutan and star apples - all given the island's abundant rainfall and constant tropical temperatures.

Although all the islands can be visited by the supremely beautiful

chows that are as ubiquitous here as they are on the Kenya coast,

a short stopover from Mombassa will probably only allow time for

an exploration of the main town and the nearby clean, coconut

fringed, sandy beaches.

The old Stone Town, now undergoing careful restoration after years of neglect, is an historical and architectural gem, arguably the most important monument to Swahili culture there is. Until early this century, Zanzibar Town was divided in two by a sea channel, crossed only by two bridges. The houses of the rich - generallythe merchants of Arabian and Indian extraction, the colonialists and administrators - were built of durable materials nearest to the harbor. The houses of the poor - almost all laborers of local extraction - were built of mud and wattle "on the other bank" (Ngambo ya pill) of the sea channel. Even after it was filled in, the divide remained until the Revolution, when housing improved and it became politically correct to live in Ngambo. Now, however, great efforts are being made not only to restore the buildings but to subsidize ordinary people to live in them and use them as real family homes.

There are so many fine buildings in Stone Town that is impossible to describe them all. Some are very obviously Arab inspired, with relatively plain facades (but do look out for the intricate Islamic carvings on the doorways), cool inner courtyards, and plain outer balconies where the men could entertain one another. The Indian houses generally have balconies protected by screens and their doors are typically adorned by elaborate brass work.

As you enter Stone Town from the seaward side you cannot miss the imposing facade of the Old Fort, a monument to the unhappy years of Portuguese rule. Next to this is Beit al Ajaib (the House of Wonders) a positive jewel of a building, three storeys high, with deep verandahs and a clock tower. Built in 1883, for Sultanate Sayyid Bargash, it is lavishly decorated with steelworks imported from England which, ironically, later withstood bombardment by a British gunboat.

Much less grand, but equally irresistible, the Central Market was erected in 1904. Almost always bustling, it is used mostly for trade in fruit, vegetables and spices but twice a week there are antique and bric-a-brac sales where some beautiful items can be found.

Although the majority of the population is Moslem, there is complete religious tolerance with Christian and Hindu festivals being enjoyed as well as those of Islam. Next to the Market area, Christ Church Anglican Cathedral, begun in 1873 and consecrated in 19003, is an impressive reminder of the British era. Nearby are the Hamman (baths) commissioned by Sayid Bargash (1870-1888) for public use.

Further into town is Gizenga Street, with its colorful shops. It

also boasts a Hindu Temple and St. Joseph's Roman Catholic Cathedral.

Romanesque in style, it dates from 1897. Look out also for the

Malindi Mosque, a much older building, frequently enlarged and

still one of the principal Friday mosques. Nearby is the unmissable

Itnaasheri Dispensary. Presented to the community by Sir Tharia

Topan, a Khoja Ismail Indian, it was intended to be a hospital

but became a dispensary when Topan died. The incredibly intricately

carved facade is sadly neglected but plans are well advanced for

its total restoration.

Zanzibar town can hold the visitor for days, but do not neglect the quieter rural spots. There are two forest reserves where rare trees complete with red colobus monkeys, the small Zanzibar leopard, duiker and sunni for attention. Visit the beaches - the ones nearer town boast all the modern sports equipment you may desire, the remoter ones offer unbelievable calm and tranquillity. There are ruins at almost every turn, many being far older than anything you may have seen in Stone Town.

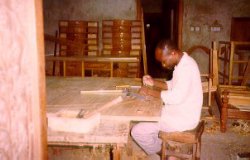

Buses and taxis are available, but if time permits, try Zanzibar's most common form of transport - the bicycle. Often supplied with large, locally woven panniers to carry camera and picnic, they allow you to the freedom to stop at will, to watch the roadside craftsmen, the boat builders and fishermen and to talk to Zanzibaris. Most speak at least a little English, although the official language is Swahili. You will be surprised how far a cheerful "Jambo" (hello) will get you. Young boys will delight in showing you how they catch octopus and everyone will want to show you their shell collections, orhow they make their baskets or fishing nets. Just one small word of warning. Haggling is a national pastime and it can be protracted, but it is always good nature. If you make a deal too easily, you may have made a Zanzibari a little richer financially, but you will most certainly have spoiled his day.

go back

go back