Master's thesis 2006

MA Communication Design

Saint Martin's, London UK

This thesis is © copyright Alex Kateras 2006. Artwork is © copyright the artists.

In a cultural landscape of hyper reality, branded lifestyles and 15-minute fame, one's subconscious receives thousands of advertisements a day. It is through this daily diet of propaganda that we shape our minds as we grow up. The desire we feel to make a mark on this world leads us to exciting new innovations on many fields, particularly in art and design.

Is graffiti art a direct result of post war advertising?

Is it a coincidence that graffiti was spawned in New York, arguably the world's most advertising saturated and simultaneously most media savvy city? One can argue that graffiti is the by-product of a society inundated with advertising. After all, both seek to do just that. Advertising and graffiti function on a Phenomenological dimension to awaken the viewer's curiosity. On one level they rely on the sheer amount of coverage and penetration, and on a deeper one they rely on the quality of the delivery to embed themselves into the human consciousness.

The aim of this dissertation is to explore the deeper affinities and differences between advertising and graffiti on a theoretical level but similarly look at both these realms in relation to other modern forms of expression such as graphic design, illustration, stenciling, stickering, and subvertising.

Through individual research, and by looking at various theorists I will attempt to establish some points of contact between the two and investigate the ways in which they play a role in each other's existence.

I will look at past movements and contemporary artists, and what methods they employ on a day to day basis to achieve their goals, as well as look at past movement in order to illustrate my argument.

The aim of this dissertation is to establish some points of contact between the worlds of graffiti and advertising. It will be a study into the ways that various social and cultural institutions interact and feed off each other. In this instance, the focal point is to what extent advertising played (and plays) a role in the inception and evolution of spray can art as we know it today. Is graffiti a direct result of advertising?

It is a subject that interests me not only as a practicing graffiti artist, but also as a consumer simultaneously skeptical of and fascinated by the advertising world. Advertising plays a major role in the formation of one's self, and it is through these perceptions and values that we see the world and others. The media, with the wide array of stereotypes and opinions shape our psyche, so naturally it is interesting to explore how one operates in view of our collective 'education'.

My suggestion is that graffiti emerged as what it is today through a lack of innovative ideas in the art world at the time, coupled with the effect of advertising on young children, manifested through the scribbling of one's name all over town. Furthermore, I argue it is no coincidence graffiti was spawned in New York as it is a city inundated with the media, and as such its population is subject to a different set of values and realities than say, Kansas City, a more rural and agricultural city, and certainly one with different values and priorities.

I will argue these points by making references to thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci and his hegemony theory, Henry Jenkin's work on textual poaching through the work of Michel de Certau as well as Walter Lipman, Noam Chomsky and Reinhold Neidbur. Furthermore I will look at suggestions by Nancy MacDonald and her work through her seminal book: 'The Graffiti Subculture' to explain the values that galvanize graffiti and its practitioners. At the same time I will discuss the advertising perspective by looking at the work of Vesterggard and Twitchell.

The first chapter will lay the theoretical background by talking about the role of advertising, propaganda and art in shaping the collective consciousness of a society, with a particular focus on New York, while the second chapter will delve into modern graffiti practices and advertising methods with emphasis on artists such as Banksy, La Mano and Pixel Phil. In addition, I will discuss the effects of modernity on futurism, pop art and Impressionism in order to illustrate how external stimuli provide the artist with inspiration. This evidence will support my argument and will map out a pattern which will better help us understand the subject.

Advertise: 1. (verb) Make known to the public. 2. Stress the good points of a (product for sale).

Advertising has come a long way from the archaic methods of attraction. Long gone are the times of fact-based advertising. Instead we have moved on to the aesthetisation of commodities, and consequently a world in which the promise made by the seller, of love, eternal youth and a fantastic bottom turns people into neurotic obsessive-compulsive consumers with a penchant for instant gratification and a 5-second attention span. The advertisements sell a way of life, not a product; in fact the ad itself becomes the object of aesthetisation.

Gradually, over the decades, fertile creative minds have gravitated towards the advertising industry, realizing that in advertising lies an art of communication, and that it can generate 'big bucks', rivaling the bohemian-type artist mode of creation. It has given otherwise disenfranchised artists a chance at making money out of their craft. Ads become much more than just ads, they incorporate art of all kinds to appeal to all tastes, using strong cultural signifiers that evoke certain emotions in the viewer (See Figure 1). They are like an exact science; they employ psychologists, behaviorists, and all kinds of experts from different fields to pinpoint the moment when a mind will be ready to respond to all these messages.

Advertising is made up of noncommercial and commercial advertising. Noncommercial advertising would be the various ads from government agencies, NGOs, organizations and societies to citizens.

Commercial advertising includes prestige advertising and industrial advertising. Prestige advertising is usually used by companies to publish annual profit reports and various other news in Sunday newspapers, and is mainly full of factual information. Even though this information will eventually reach the shareholders by mail anyway, it is considered to be a good tool for creating "long term goodwill with the public rather than at an immediate increase in sales" (Vestergaard and Schroder, 1985: 1) as outlined by Vestergaard.

Industrial advertising, on the other hand, is aimed at other companies; that is to say there is equality between the buyer and the seller as both are professional, as opposed to commercial consumer advertising aimed at amateur buyers, or the individual consumer.

Commercial consumer advertising is the one that makes the most impact and generates the most profit, and it is the more ubiquitous of the aforementioned types.

When talking about advertising it is important to note the presence of the word 'brand' in relevant literature, as it is a word that has changed the way companies operate in their totality. Some early branding took place as early as the end of the 19th Century, where in a sea of new products, all of which were identical, a company had to give itself a name, an image, a logo. "The first task of branding was to bestow proper names on generic goods such as sugar, flour, soap and cereal, which had previously been scooped out of barrels by local shopkeepers. In the 1880s, corporate logos were introduced to mass-produced products like Campbell's Soup, H.J Heinz pickles and Quaker Oats cereal" (Klein, 2000: 6). (See Figure 2). This type of branding differs from the type of branding associated with the 1990s branding mania, in that it was a method to just stand out amongst a plethora of products with no names or history.

Advertising is like propaganda, because it makes it self ubiquitous, while the message it carries is one that has been born out of ulterior motives by people who want to make money and maintain the status quo. Alongside the news, advertising is a tool that shapes public opinion.

Advertising, as it was known many years before, plays a central role in society, not simply just as a way for companies to sell products but also as a way to disseminate ideas and concepts. It's the tool that the dominant elite employs to promote agendas and maintain the status quo. To keep things how they want to.

Large conglomerates and governments have always been in the forefront of this as it is logical that the "people who own this country ought to govern it" in the words of John Jay. Reinhold Neidbur stated that "the common interests very largely elude public opinion" and so a specialized class have to make sure these interests are served for the welfare of everyone. Understandably, this specialized group has to divert and 'inform' public opinion about issues that are too complicated for the average man to comprehend, because the average man follows not reason but the heart and blind faith. It is a logical step, and has been since the first power structures of the cavemen and tribesmen. Noam Chomsky argues that propaganda is to a democracy what violence is to a dictatorship. Propaganda, however, is more than that. It is through propaganda that a capitalist economy can survive. By setting up a structure that depends on people perpetually consuming, an economy can flourish. And propaganda, one might argue, is now thought of as advertising.

Antonio Gramsci, the Italian thinker, referred to this as the negotiation of consent.

"Dominant groups in society, including fundamentally but not exclusively the ruling class, maintain their dominance by securing the 'spontaneous consent' of subordinate groups, including the working class, through the negotiated construction of a political and ideological consensus which incorporates both dominant and dominated groups" (Strinati, 1995: 165).

This consent is manufactured through the use of ideological state apparatuses such as newspapers, religion and the media as well as advertising, which serve as mouthpieces for the dominant elite's agenda. It is through advertising that youth culture has manifested its more creative side in the form of subcultures such as the Punks, Mods, Rockers and of course graffiti art. It is also through advertising that we see the beauty myth, and the celebrity culture at its highest, The American Dream. It is through this that the dominant elite can engineer the 'manufacture of consent' from the 'masses' and keep the capitalist machine going, according to Walter Lipman. By diverting the public's attention from matters that are touchy, the government selects what news will be consumed.

In his book 'Manufacturing Consent', Noam Chomsky persuasively argues that news gets filtered through such state apparatuses and only the news deemed to be in accordance with official government policy gets shown. Chomsky brings up the East Timor conflict as an example. Indonesia, as an official U.S ally and aggressor in the conflict received no media coverage, in atrocities that were in the same league as the ones in Cambodia. The only difference being that Cambodia was an official U.S. enemy, and so the Khmer Rouge were duly demonised in the press. He also argues that this practice is so embedded into the modus operandi of society that most people are not even aware of its existence. This kind of propaganda, or lack thereof, is central to a regime's survival. The media must fall into line in order to secure the consent of the public.

Some people may argue that this is necessary for the overall good of the nation. It goes without saying that the majority of people are neither interested nor equipped to deal with such realities, and that certain aspects of the administration must be kept hidden. 'Democracy and anarchy are only separated by a thin line', would be likely to be uttered out of someone's mouth, and true enough, the notion that a country must stand united in the face of adversity does stand to scrutiny. However, when the threat of that enemy gets blown out of proportion on such a scale (according to a number of liberals including Chomsky, the Cold War, only served the purpose of pushing the arms lobby, and thus the U.S economy, while the real threat of terrorism is only known by top government officials) for means that serve only a small minority of 'have mores', then it is morally wrong for a government to misinform and mislead the public on such crucial issues as decisions on whether to go to war. The public, like Reinhold Neibur argues, keeps itself sedated with popular culture, the most sophisticated piece of propaganda ever invented, and of course this indoctrination gets well under way from the moment children open their eyes.

Young children are usually the target group most swayed by advertising with the 'nag' factor increasing consumer spending. Ad agencies now try to 'get' young children from a young age to instill brand loyalty, and ads for children now have reached such levels of unashamed covert and overt persuasion techniques that some countries have refused to screen ads for children at certain times while stricter measures have been implemented. The youth market takes the lion's share in profits.

Identity plays a central role in modern times, and ad agencies, as we know, sell lifestyles and identities in the form of popular culture.

As Vestergaard points out in relation to ad agencies

"One of the assumptions underlying their strategic work is that advertisements should work on each reader's need for an identity, on the individual's need to expose himself/herself to lifestyles and values which confirm the validity of his/her own lifestyle and values, thereby making sense of the world and his/her place in it. What we are faced with here is a signification process whereby a certain commodity is made the expression of a certain content (the lifestyle and values)." (Vestergaard and Schroder, 1985: 73).

In this case the commodity is the spray can, and even though that commodity itself is not the bearer of great wealth, the association it has with elements of rebelliousness and beauty makes it very marketable.

It is worthwhile at this point to establish the lines of demarcation that separate the various terms used to describe graffiti. Aerosol art and graffiti seem to be the two most prevalent terms. However some people contend that aerosol art sounds too commercial because people immediately think of airbrush, while others maintain that the negative connotations 'graffiti' has acquired has slowed its progress. Within the term graffiti, one encounters the graffiti writer and the graffiti artist, with the former being the 'pure' element since the writer's work is done almost exclusively illegally. 'Street art' is a relatively recent addition to everyday palaver, and mostly refers to latter-day stencil, poster and sticker art and carries political connotations.

As advertising and graffiti rely on the amount of coverage or penetration, coupled of course with the quality of the delivery, it is easy to see how these two entities are so much alike. "As commercial logos lose their shine and cities start to look the same, graffiti street signs and logos become a symbol of individuality, fulfilling man's basic urge to leave a trace on the world" (Manco, 2004: 43).

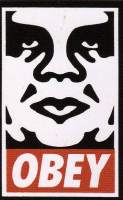

If a tag or a logo can be reproduced enough times and it becomes recognizable by a large section of the community then it becomes part of the social and natural landscape and it is referenced, it becomes instantly embedded into the mind. Obey Giant (see figure 3) for instance is an interesting case. Artist Shepard Fairey came up with the original idea of turning Andre, a Russian wrestler into Andre the Giant and adding the Obey caption, which is meant to play with people's perception of reality. Originally done as a stencil in his neighbourhood, it was a jibe at a local group of skateboarders from his area, and the caption read: 'Andre has a posse".

Some people upon looking at an Obey Giant image are unsettled by it and perhaps a little scared. They feel uncomfortable because they expect it to be an advertisement, and so find it hard to make sense of why it's there. What is especially bizarre is the fact that people around the world have adopted that image and they themselves go out and paint it in their respective countries; a piece of underground art so popular it is being reproduced by scores of artists of various disciplines. Shepard Fairey has managed to do what most advertisements fail to do with a significantly smaller budget; to reawaken someone's curiosity about their urban environment and make them question certain values.

Graffiti: (noun plural) words or drawings scratched on a wall etc.

Without going too much into detail about the origins of graffiti, suffice to briefly outline the driving force behind such a strong cultural phenomenon. Graffiti is galvanised by the 'fame game'. The individual's goal is to make himself known to as many people as possible. In New York in the early 1970s this was facilitated by the relative ease with which trains got painted.

People from all over New York could see what someone had done in The Bronx, an otherwise ordinary person, who probably was not as interesting as his art. The fact that graffiti was practised on the subway system of New York shouldn't perhaps come as a surprise, indicating that mobility may have been an element that graffiti writers subconsciously gravitated towards. Graffiti was also a way out for young adults to escape the mundane existence of everyday life and possibly a career in crime and drugs.

Your tag as your alter ego, the name by which most people will know you, rather than your Christian name, takes a life of its own. It becomes something separate, something that being in the public eye also gets observed, scrutinised and admired. The 'fame game' brings popularity, a sense of self-esteem, friends and recognition from people you don't even know. As a graffiti writer, one is driven by the desire to be known and be respected. "Fame, respect and status are not naturally evolving by-products of this subculture, they are its sole reason for being, and a writer's sole reason for being here" (MacDonald, 2001: 68) according to MacDonald.

Advertising has played a decisive factor in the formation of graffiti in two major ways. Ideologically, it manifests itself in the form of fame. Competition among a wide variety of writers and artists to contend for respect in the form of subcultural capital and perhaps financial capital. The other influence is the visual manifestation of the company through the word and image and consequently becomes the visual factor. In this, one can clearly familiarize in graffiti's letter-based palette of words and tags representing each 'brand' of painter, with the subsequent advent of postering and stickering to which I will be referring later. These are precisely the premises on which advertising works; products need fame in order to stand out, something we see in the omnipresence of ads, while respect translates into the tangible product, the actual quality of what is being flogged.

I suggest that young children in New York, and teenagers in particular, having been exposed to the calibre of marketing and advertising over there, may have created just that; the need to stand out in a visual landscape replete with popular culture, advertising billboards and signs of all types, regurgitated in the form of graffiti art. It's not hard to imagine how a young mind can try to emulate what it sees on the television, particularly in New York where popular culture and advertising is at its best. Barry Dawson says that "New York is the world capital of street graphics -- the urban ephemera of signs, symbols, graffiti, murals and advertising" (Dawson: 2003: 7). Since the time of pop art and before, New York is considered to be the most media saturated city. Given that "consuming ads is how all of us have spent most of our time" ( Twitchell, 1996: 4), and that teenagers in particular are the most conspicuous consumers of popular culture, one can draw a parallel here.

Michel De Certeau had touched on the notion that consumption of culture involved the active participation of the consumer. Henry Jenkins, drawing on De Certeau's work further argues this, in his book 'Textual Poachers'.

"Far from syncopathic, fans actively assert their mastery over the mass produced texts which provide the raw materials for their own cultural productions and the basis for their social interactions. In the process fans cease to be simply an audience for popular texts; instead, they become active participants in the construction and circulation of textual meanings" (Jenkins, 1992: 24).

Arguably, there is little difference between a Star Trek fan who produces 'slash' comics, and a young kid being influenced by the millions of signs and words he sees each day, and coming up with his own alter-identity, his tag that he will embed on as many surfaces as possible. The same principle applies within these parameters it would appear. Young kids playing with the raw material readily available from popular culture, and subverting their meanings. Not implausible. Clandestine and non-sanctioned art in the wrong places and with wrong messages, subverted logos and brands in the form of tags and pieces.

As Tristan Manco explains:

"Graffiti often borrows from the aesthetics of signage and the jargon of advertising campaigns. The drop shadowed letters of shop signs, the wild vernacular lettering styles of naïve hand painted signs and neon lights are just some of the city signs that have influenced graffiti lettering, composition and tactics" (Manco, 2004: 11).

As illustrated above, this is a manifestation of the visual dimension of graffiti. Similarly, in a cycle in which it's hard to distinguish art imitating life or vice versa, one saw the evolution of advertising moving into a world of branded lifestyles, while at the same time saw graffiti moving towards a logo-based tag rather than a classically letter-based one. Something that in its own way will stand out among a plethora of tags and standard graffiti art (the same of which can be said about advertising and the advent of the 'brand' in the early 1990s), logos are a way to make products more appealing.

Essentially, one can argue, graffiti and advertising are the same ball game, only difference being the league they are in. Commercial consumer advertising is propelled by immediate financial profit and mediated by boardrooms and stockholders. It aims at exposing that product in an appealing way, and doing it so as many people are aware of that product. Graffiti is a tool used by individuals with their own agenda, one however that doesn't include profit as its foremost target. The main agenda of a graffiti artist is exposure by means of guerrilla tactics.

There is a differentiation between classic hip-hop type ("modern") graffiti, where people have tags and want to get their tags in as many places as possible, and the latter-day street art, where people may have tags, but deploy techniques such as stencils to pass a message somewhat more profound than the simple tag. (See Figures 4 and 5). "Whereas hip-hop graffiti evolved from the written letter, the majority of stencil graffiti is essentially iconographic or pictographic" (Manco, 2002: 19).

These artists call on phenomenology to convey their message. The process of reawakening one's awe in their environment has been with us for a long time, but in the context of graffiti it is a practice which has been employed slowly but steadily over the years, with advocates such as Dave Kinsey, Shepard Fairey and Banksy. This cross-fertilization, or cultural cannibalism, is a process that involves a continuous give and take by both entities, and a process that dilutes and expands the meanings of symbols.

However, one must wonder, what degree of independence and how much actual original thinking one has from the media landscape of popular culture and advertising, and to what extent one is influenced and swayed by these messages. Is graffiti really a direct result of advertising or is it simply just poaching from advertising? How much does graffiti owe to advertising and popular culture? Perhaps the only way to get a glimpse of the truth lies in the past. By looking at life and art before, one might begin to discern a pattern in the way these movements evolved and thus give us a clearer insight into the inner mechanisms of this subculture.

The second chapter will look at the evolution of art as a natural progression of the constant changes in the social-political milieu, and in particular I will discuss the revolution of impressionism, futurism and pop art in order to illustrate my argument in more detail. Furthermore, I will look at some of latter-day techniques and methods used by street artists and graffiti writers alike.

When comparing the worlds of advertising and graffiti, it is imperative to look at some past styles and movements. Inevitably, impressionism creeps up in the discussion a number of times, most notably in that it revolutionized the way people perceived art by creating its own rules and in doing so, bringing down established methods of applying paint on a surface. There were several factors that converged to mould the course of history; availability and quality of materials at the time was going under drastic change, while artists began depicting cafes, parks, ballets, parks and racetracks in a conscious effort to capture the visceral qualities of life at the time.

Photography at the time was gathering steam as a tool to be employed by artists.

As Callen duly notes:

[The] "rise of photography from the 1840s, had, for artists complicated the issue of the illusionistic representation of reality, provoking some artists to attempt an even more fastidiously representative style of painting. On the other hand, for others the very existence of the photographic image was a release from the demands of painstaking representation of the visual world, leaving them free to pursue a more personal reading of nature, like that of the impressionists. Their method was based on the translation into paint of the individual artist's optical perceptions, a phenomenon beyond the camera's reach. It also freed artists to explore the problems of painting itself." (Callen, 1982: 28).

The impressionists' work was influenced by the advent of photography, and even though it wasn't the only influence, one can argue that it was important enough to bring about such changes. The industrial revolution spurred many movements to life, and one of these was futurism; a strange mix of technophiles and radicals.

Futurists represented a new strain of literary and artistic thought. Mainly based in Italy, these artists and writers of which we can single out individuals such as Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini, Carlo Carra and naturally F.T Marineeti, were inspired by technology and the prospects of a fully integrated mechanical world. Despite their controversial ideas and theories on women, religion and museums, their ideas paved the way for a new set of paradigms.

"Living art draws its life from the surrounding environment. Our forebears drew their artistic inspiration from a religious atmosphere which fed their souls; in the same way we must breathe in the tangible miracles of contemporary life-the iron network of speedy communications which envelops the earth, the transatlantic liners, the dreadnoughts, those marvelous flights which furrow our skies, the profound courage of our submarine navigators and the spasmodic struggle to conquer the unknown. How can we remain insensible to the frenetic life of our great cities and to the exciting new psychology of night life; the feverish figures of the bon viveur, the cocotte, the apache and the absinthe drinker?" (Apollonio, 1973: 25).

Futurism, despite all its shortcomings (futurism was closely affiliated with Mussolini, and its manifestos quite literally rejected everything and anyone, and thus was largely relegated to the role of the pariah) was a truly groundbreaking movement, in that it rejected the past wholly, and in turn embraced everything that was new. The speeding car, the tall skyscrapers, the trains, boats and airplanes were all turned into objects of idolatry, one could argue; they were the physical manifestation of their desire, and it is hard to imagine a 1910s world in which futurism didn't exist. It was an inevitability, given the fact that industrialization was sweeping the world, and its rippling effects were impossible to ignore. This should strike a resounding chord in our subject, having in mind that graffiti emerged as a product of its time and environment.

At around the same time of the Futurist movement, Toulouse Lautrec began establishing himself as an artist. He was the pioneer of the poster art movement, an influence that stemmed from the growing number of advertisments during that era. It was around that time that brands began taking hold of the social landscape, as I mentioned in chapter 1, and naturally it was an avenue, as yet unexplored, that attracted Toulouse Lautrec.

Figure 6: 'Marilyn', Andy Warhol. 1961

Figure 6: 'Marilyn', Andy Warhol. 1961

Representational art had taken a back seat to a new form of drawing that allowed the artist to freely experiment with what he perceived as important. Freed from the shackles of conventional methods of representation, these artists steamrolled the way for pop art, perhaps the first movement to dispose of traditional mediums, and subject matter as shown on figure 6.

In pop art one sees the first nod to popular culture and acceptance of the so-called lowbrow denominator that theorists ranging from Marx to Baudrillard described as unbearable. This is summed up very concisely by Amaya, who claims that:

[Never] "before has the human eye been so assaulted by images printed, painted, photographed, stenciled and otherwise copied, both moving and still. Because of the immense power and spread of advertising and mass media communications through publications and television since the Second World War, we have taken for granted a whole new set of signs, symbols, emblems and imagery, which has settled into our subconscious as a commonly shared visual experience." (Amaya, 1965: 11).

Just like pop art, graffiti is a true post-modern entity, in that it unashamedly borrows from the 'supermarket of style', regurgitating elements from popular culture and advertising, and through this 'textual poaching', giving new meaning to otherwise obsolete or indifferent elements.

Graffiti is advertising; the tag is the ad and the writer is the company. Furthermore, the fact that graffiti is mainly practiced with spray paint is not incidental. In a world where everything gets trivialized within a matter of seconds and where art is so ephemeral, what better tool to use for instant art than the spray can, its use rendered obsolete as soon as the paint inside runs out; disposable tools for disposable art. Furthermore, the nature of graffiti means that public space is reclaimed for the purpose of creating art that is not meant to be there; it isn't sanctioned by any governing body, and evidently not by the owners of the vandalized property. Paradoxically, graffiti, which prides itself in being one of the only true subcultures in so much as its practitioners are in it not for the money but for the fame, could in fact be, a direct result rather than a by-product of advertising, the glaring antithesis to notions of purity and altruism.

Graffiti is advertising for the disenfranchised, for the people who have grown up in a visual landscape of materialist consumer culture, full of signs, brands and that ever-present invitation to make money and be someone. It's subverted advertising by the 'masses'; a response to the establishment that propaganda cannot only be used by the dominant elite to promote its capitalist agenda, but by ordinary folk too.

Graffiti first came out of the ghettos of Philadelphia and New York and soon evolved into what it is today. Stenciling, on the other hand, was widely used in France during the post-war years, and the walls in Paris are a testament to that, especially during and around the May 1968 riots. Most were politically centered and included mainly slogans and some images. The spray can itself is not a new tool for those ends, as it was used to write slogans and propaganda for decades before it acquired its artistic status.

Even though graffiti for political ends is not new, some of the tactics and methods used have changed over the years. Graffiti still retains its outlaw status and as such is still considered a deviant subculture. Nevertheless, it is subject to the laws of the market and has become, to a degree, assimilated by the mainstream. This means that it has had to come up with new ways to operate in stealth and has developed new methods that make it easier for writers to 'spread' the message, some of which include stickering, postering, stenciling as well as the Internet and fanzines.

As fences have become higher, security cameras have become more ubiquitous and police have wised up, so have the rules changed. Necessity is the mother of invention, and because graffiti has had to evolve, in a way, its parameters too have shifted in accordance with the surrounding environment and the sociopolitical milieu. Politics and morality seem to be more central in the 'new school' artist's agenda. Social, political, economical and environmental issues have taken center stage in the past decade that have molded a new reality; a 'new world order' as it were.

Global warming, a new struggle in the Middle East, and the effects of globalization have given fuel to a new set of street artists such as Banksy, who prefer to convey a concept not just a name. They poke fun at the authority figures by hijacking the dominant culture's mouthpiece; propaganda.

A growing number of writers now reject the very existence of advertising on the grounds that it monopolizes the visual landscape while promoting its ruthless agenda of moneymaking ideals through the projection of 'immoral' stereotypes.

This new type of 'brandals' feel that corporate advertising has become too big. "Reclaiming the city space is often seen by graffiti artists as their main mission, either as a reaction against consumerist advertising or a need to make a personal mark on their environment" (Manco, 2004: 11). As a reaction to this rampant advertising that pervades every corner of life, a magazine called Adbusters emerged in the mid-1990s as the brainchild of Kalle Lasn, a former advertising executive who believes that advertising and consumerism are a cloak for deeper means and through the art of 'subvertising' manages to create interesting cultural artifacts.

Some of these attitudes may be traced back to the RECLAIM THE STREETS movement that began in the early 1990s. RTS was molded out of a collective disillusionment with the then status quo, and it comprised several types of activists, ranging from ravers to graffiti writers. They advocate direct action in a peaceful, carefree and cheeky manner "There was the trashed car on Park lane symbolizing the arrival of Car-Mageddon, DIY cycle lanes painted overnight on London Streets, disruption of the 1993 Earls Court Motor Show and subvertising actions on car adverts around the city". Some of their most memorable stunts included blocking the M11, and several other crucial arteries, as well as participating in protests in Nigeria over Shell's involvement in the murder of 8 of its workers.

Other examples of direct action taken by independent groups are Backspace, for instance. As a group of artists, poets, musicians and IT wizards, they provided free access to technological equipment and staged events in the Starbucks shop they took over. The point that people tried to emphasize was that standing up to injustice could be achieved through means that don't involve violence.

Ironically, the use of aerosol seems to have been largely ignored by the environmentalist groups that graffiti practitioners have aligned themselves with, something that perhaps hints at a dash of double standards. Nevertheless, graffiti and latter-day street artists have embraced the growing concern over the environment, arguably the world's biggest threat, with terrorism coming in at second, according to prince Charles.

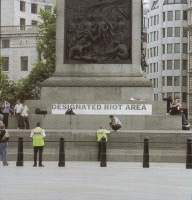

Banksy is a particularly interesting case, as he stands alone in his endeavor to embarrass the establishment through his stencils (See figure 7). Some artists seek to make use of the space as a context for their work to gain significance. Banksy is an example of an artist who has adopted that notion. One of his most ambitious missions included writing in big letters in Trafalgar square: 'DESIGNATED RIOT AREA' (See figure 8). "By creating art in public spaces, artists draw attention to city spaces and re-examine areas thought to have had no artistic interest. They challenge the ownership of space by councils and corporations. They battle with the giant illuminated billboards, themselves just as much visual invaders as graffiti" (Manco, 2004: 11).

If the current trend of street art is anything to go by, then it is clear that advertising and popular culture have had a tremendous effect on latter day street artists. It's akin to an intifada of some kind, a visual attack stemming from social unrest by large portions of the population, mainly the dispossessed and the civic conscious. This briefly brings us back to the topic of 'manufacture of consent' in as much as it has seemingly failed to do what it purports. Some people have realized that the consent is secured through the apathy and laziness of ordinary people, and as such have decided to fight propaganda with propaganda through art.

As mentioned in chapter 1, graffiti has moved toward a logo-based focus. The tags have become such a common sight, that something totally different has to be created in order for it to stand out; an image that will stick out like a sore thumb amongst a plethora of tags and scribbles (See figure 9). Artists like La Mano from Barcelona were quick to subscribe to this notion as seen in figure 9.

These logos are instantly recognizable, like the corporate logos themselves, and it is fast becoming the norm for an artist to experiment with such techniques if he wants to be heard. By incorporating signs and symbols used everyday, graffiti artists can 'talk' to the public by using a common language that will be understood by the majority. "They have appropriated certain aspects of branding, such as local and global campaigns and the use of repetitious logos, to get their ideas across but they are more like artists' own labels than graffiti super-brands -- more human and genuine than commercial logos" ( Manco, 2004: 43).

Clearly, graffiti has evolved with the times. Postering and stickering, which are hallmarks of advertising methods are being 'hijacked' by artists. The digital age with all it entails has provided sufficient inspiration for artists such as Pixel Phil, whose methods consist of stickering pixilated images of desktop icons and such other imagery to portray the growing digitalization of the world (see figure 11). The magazines, and increasingly the Internet are becoming the new mediums with which artists from everywhere can make themselves known to a wider public, thus lending credibility to the notion that graffiti has become a truly global culture and a shared experience.

Viral marketing has 'infected' graffiti as well, rivaling the impact of magazines. The Internet has allowed for a greater communication and dissemination of material, meaning that someone in Japan can instantly see art produced on the other side of the world, can exchange opinions and even play an on line game called "Bomb the World" in which you can paint virtual trains and see what someone has painted miles away (See figure 12). More recently, Ecko's videogame called "Getting Up", released by Brady Games, the same company that introduced "Grand Theft Auto" to teenagers, was vilified because it promotes 'anti-social' behavior through its objective, which consists of tagging and 'bombing' as many surfaces as possible.

Practiced outside the confines of conventional channels, graffiti requires only time and interest by anyone. The one thing that remains clear is that graffiti is a potent tool. It is mainly used by the masses, despite the fact that corporate environments have tried to co-opt it, and seems like it will continue being the preferred alternative for the disenfranchised. What is certainly true is that there is no longer anything left which is not 'up for grabs' in this world of instant gratification and trivialization.

In this dissertation we have examined the suggestion that graffiti was a direct result of advertising and the effects of a world over-saturated with popular culture imagery with an emphasis on New York. Having looked at the worlds of advertising and graffiti separately, I have outlined their raison d'être, and the forces that propel them, while comparing the different elements that bind them together.

As with past movements such as impressionism, futurism and pop art, graffiti was a response to the changing norms of time. While photography, the increasing industrialization of the world and popular culture became the central aspect of these movement's existence respectively, I have argued that advertising was the factor that spurred graffiti into prominence through a barrage of constant messages. Ideologically, graffiti becomes a visual manifestation of man's desire to leave his mark on the world, something that is the hallmark of advertising practice, while visually (logos, signs, brands), advertising has provided the 'raw materials' as it were, with which writers become known.

The desire instilled early on in our lives by the advertising agencies to consume, and through consuming becoming someone popular, manifests itself in the form of tags. Tags are self-promotion for the individual, the name of the 'brand'. "A tag is a small advertisement for an artist -- a logo for an ego" (Manco, 2004: 43). During the years, graffiti has evolved, and so have its aims and methods. Instead of just writing your tag in calligraphic letters in any surface, writers now choose to create image-based logos many times with a message; their choice of what to put up changes accordingly with time.

New issues, such as globalization, global warming and corruption become the material that artists choose to represent, by subverting signs, logos and cultural artifacts to humorously point out paradoxes in society, while the digital age brought about its own revolution in terms of fame. The Internet and the magazines have become the new trains and walls of the subculture, mirroring the overall trend in society. One can draw a useful parallel here, with the evolving democratization of information, through the advent of the internet and most importantly open source information, and the democratization of art, as it were. Graffiti is free, no entry fee is required to view it, while open source has allowed people to obtain free software and data that constantly pushes the limits of human creativity. Indicative of this is the fact that open source info is so popular in Sweden that having loopholed several laws, a group of Internet pirates may be running for office in the next parliamentary elections. This provides us with a clear insight into possible developments and repercussions for the public. If a group -- that under California law can be put behind bars -- can legally obtain seats in Swedish parliament, then that is strong evidence that the public is ready to renegotiate its consent.

Graffiti has always been the voice of the underdog, whether on trains in New York, as stencils, tags or simple slogans.

Having established that changes in society have an impact on artists, and having examined the role of popular culture and advertising on the psyche, it is fair to suggest that graffiti is the visual manifestation of a generation that grew up on a diet of 3,000 advertisements a day and a desire to make its mark on this world. Having traced a pattern reaching back to the impressionists, we have seen the evolution of art as a reflection of changes in society. Inequalities and discontent with the status quo have been manifested through graffiti art. In New York in the 1970s the youth from the Bronx were unhappy with the meager opportunities presented to them and one way out of the maze was graffiti; a culture they could wholeheartedly call theirs. The empty promises of the ads and the celebrity culture were turned upside down, and now every child possessed his or her own 'brand'.

In the beginning of this dissertation, I suggested that graffiti may have emerged as a result of rampant advertising in New York, arguing that New York is a media-saturated city, and as such, proved to be a fertile ground for the mushrooming of graffiti. A lack of fresh ideas after pop art, and the effect of advertising on young children may have been the catalyst for the inception of this global art movement. Furthermore, I argued that a pattern was evident in the way art movements evolved and technological innovations marked an era, with reference to impressionism, futurism and pop art. In addition, I looked into the way graffiti developed as a tool for the marginalized sector to make its voice heard, by appropriating the elite's mouthpiece: propaganda, or as some people might call it; advertising. Having looked at all this evidence, and joining the dots together I can only come to the conclusion that graffiti art is the logical progression of art. A combination of art, popular culture and the guiding principle of advertising which is omnipresent.

Amaya, M 'Pop as Art' London: Studio Vista Ltd, 1965

Apollonio, U 'Futurist Manifestos' London: Thames and Hudson, 1973

Callen, A 'Techniques of the Impressionists' London: Book Club Associates Ltd, 1982

Cooper, M and Chalfant, H 'Subway Art' London: Thames and Hudson, 1984

Dawson, B 'Street Graphics: New York' London: Thames and Hudson, 2003

Jenkins, H 'Textual Poachers: Television fans and participatory culture' New York: Routledge, 1992

Klein, N 'No Logo' London: Flamingo, 2000

Livingstone, M 'Pop Art: A Continuous History' London: Thames and Hudson, 2001

MacDonald, N 'The Graffiti Subculture' Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001

Manco, T 'Stencil Graffiti' London: Thames and Hudson, 2002

Manco, T 'Street Logos' London: Thames and Hudson, 2004

Strinati, D 'An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture' London: Routledge, 1995

Twitchell, J 'Adcult USA' New York: Columbia University Press, 1996

Vesterggard, T and Schroder, K 'The Language of Advertising' London: Basil Blackwell Publisher Ltd, 1985

Contact Alex Kateras or yo@graffiti.org for reprinting information or questions.

This document is archived at http://www.graffiti.org/faq/kataras.html